Divorce and legal separation not only mark significant changes in personal relationships but also necessitate careful consideration of asset management and protection. Central to this process in California is understanding the implications of Section 2040 of the California Family Code, which pertains to the Automatic Temporary Restraining Orders (ATROS) that come into effect once a divorce proceeding begins.

Introduction to Section 2040 and ATROS

Section 2040 of the California Family Code sets forth specific restraining orders that automatically apply to both parties in a divorce or separation case, the moment a petition is filed. However, you are free to make a will or change your existing one. We will explain what else you can do. The restraining orders, known collectively as Automatic Temporary Restraining Orders (ATROS), are designed to prevent either party from making drastic changes that could impact the financial status quo or the parties’ assets during the divorce proceedings. The primary intent of ATROS is to:

- Prevent either spouse from hiding, selling, or otherwise disposing of any property—be it individually or jointly owned—without the consent of the other party or a court order.

- Ensure that all financial assets and liabilities are maintained in their status quo until a final agreement is reached or a court makes a determination regarding their division.

ATROS essentially freezes the economic aspect of the parties’ lives during divorce proceedings, ensuring that the division of assets upon dissolution of the marriage is fair and uninfluenced by any post-separation changes one party might make unilaterally.

Not Having a Will: The Implications of Community Property Laws

California’s community property laws dictate that any assets acquired during the marriage are owned equally by both spouses. This ownership structure affects estate distribution upon death, even during a divorce proceeding. If you die without updating your will during the divorce process:

- Automatic Share to Spouse: In the absence of a will, or if your existing will hasn’t been updated since initiating divorce proceedings, your estranged spouse may still inherit all your community property. This scenario often occurs because, under California law, the deceased’s share of the community property defaults to the surviving spouse in the absence of specified different intentions in a legally binding will.

- Legal Complications: Dying intestate (without a will) during a divorce can lead to complicated, lengthy legal proceedings. Your assets may not be distributed according to your wishes, and instead, they would be handled according to California’s intestate succession laws. This often results in the estate being divided in a standard way among surviving family members, which might not reflect your personal preferences.

The risk of death during divorce is not trivial. Divorce rates for younger couples have decreased, but those for age groups 45-54, 55-64 and 65+ have increased from 1990 to 2021 [DirectLink][PermaLink]. Unfortunately, in these age groups declining health may be a factor for a partner to seek a divorce: In Sickness and in Health? Physical Illness as a Risk Factor for Marital Dissolution in Later Life.

The Need for Updating Your Will

- Reflect Current Wishes: Divorce significantly changes your personal relationships and likely your preferences for who should inherit your assets. Updating your will during a divorce ensures that your current wishes are accurately reflected. For instance, you might prefer that your siblings, parents, or close friends inherit your personal assets instead of your estranged spouse.

- Protect Your Children’s Interests: If you have children, updating your will is crucial to ensure that provisions for their guardianship and inheritance are set according to your current wishes. While your spouse would typically gain custody if you pass away, specifying financial provisions for your children, and even specifying a guardian in the event of the death of both parents, is prudent.

- Assign Executors and Trustees: During a marriage, spouses often name each other as executors or trustees. If a divorce is underway, it’s advisable to appoint someone else who aligns with your current circumstances and intentions to manage your estate and any trusts you establish.

- Minimize Disputes: An updated will can help minimize disputes among surviving family members. Clearly articulated wishes can reduce misunderstandings and potential legal challenges from your estranged spouse or other relatives, thereby protecting the estate from costly and prolonged court battles.

Key Provisions of Section 2040

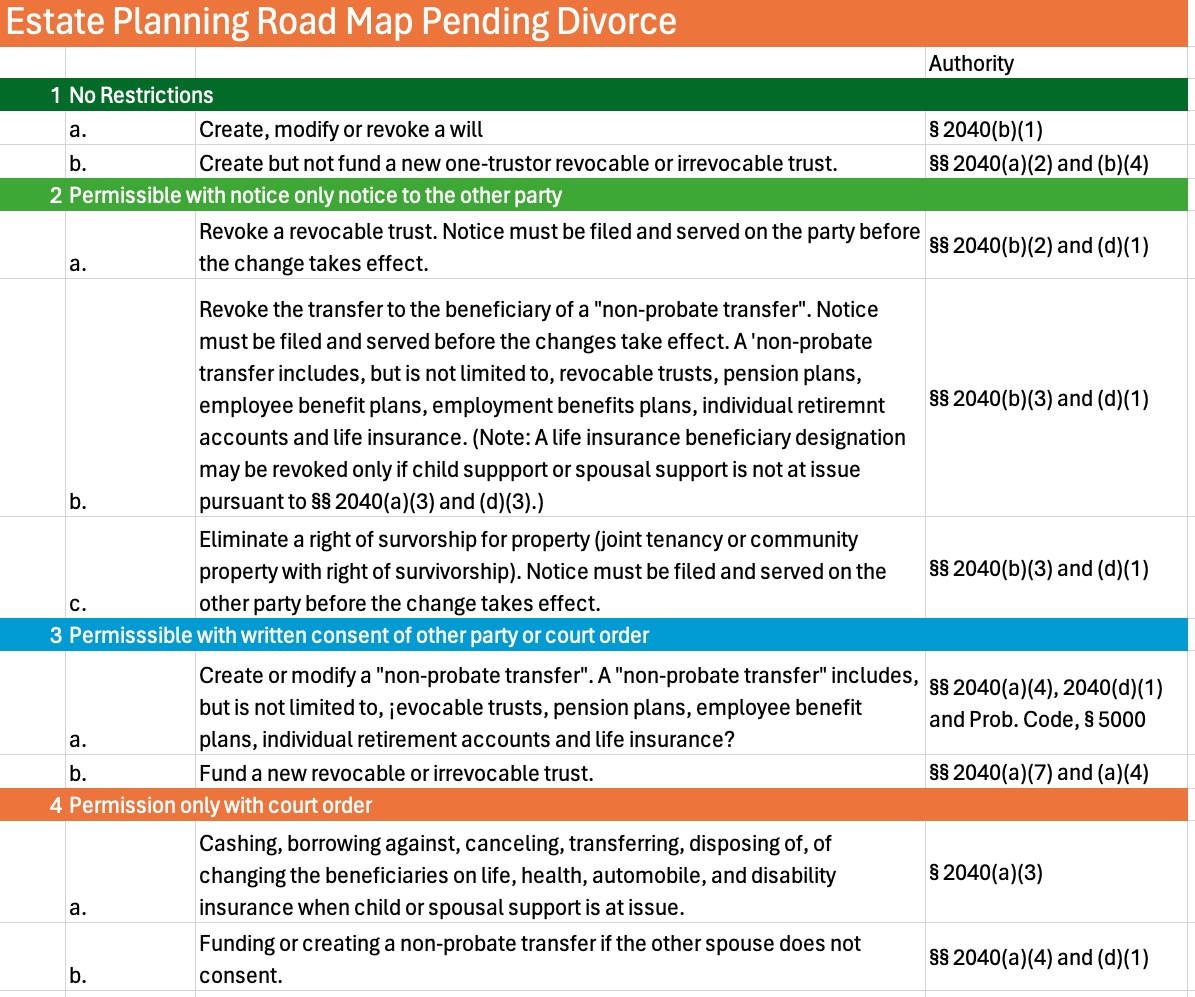

Under the framework of Section 2040, several specific actions are regulated as follows:

1. No Restrictions on Certain Actions

Even with ATROS in place, the law permits certain actions without restrictions, recognizing the need for personal autonomy in specific areas:

- Creating, Modifying, or Revoking a Will: Individuals are allowed to adjust their wills to reflect their current wishes without needing the other party’s permission or notifying them (§ 2040(b)(1)).

- Creating Trusts (With Limitations): One can create new trusts—both revocable and irrevocable; however, funding these trusts is subject to further conditions to prevent circumventing the intent of ATROS (s§ 2040(a)(2) and (b)(4)).

2. Actions Permissible With Notice

Certain significant actions can still be taken, provided that the other party is formally notified, maintaining transparency during proceedings:

- Revoking a Revocable Trust and Non-Probate Transfers: Actions like revoking a revocable trust or any non-probate transfer require that advance notice be filed and served (§ 2040(b)(2), (b)(3), and (d)(1)).

- Eliminating Rights of Survivorship: Similarly, changing the survivorship status of jointly held assets necessitates notifying the other party (§ 2040(b)(3) and (d)(1)).

3. Actions Requiring Consent or Court Order

For actions that could significantly alter the financial landscape, either the consent of the spouse or an order from the court is required:

- Modifying Non-Probate Transfers and Funding New Trusts: These actions are tightly controlled to ensure that neither party is disadvantaged by changes made after the initiation of divorce proceedings (§§ 2040(a)(4), 2040(a)(7), 2040(d)(1), and Prob. Code, § 5000).

4. Restricted Actions Requiring Court Intervention

In cases where child or spousal support issues are involved, the court takes an even more cautious approach:

- Insurance and Benefit Changes: Any decision to alter insurance policies or beneficiary statuses where support issues are present requires judicial approval (§ 2040(a)(3)).

Conclusion

Understanding the function and implications of Section 2040 and ATROS is crucial for anyone undergoing divorce proceedings in California. These regulations safeguard the financial interests of both parties, ensuring that assets and liabilities remain intact and transparently handled throughout the dissolution process. Being well-informed about these restrictions and permissions enables individuals to manage their affairs prudently during a time of significant personal change.

For your convenience, the following table summarizes the relevant subsections of § 2040 of the California Probate Code. The table is adapted from Jerome Crum, Trusts & Estates Quarterly. Winter 2008.